As I’ve written on the topic of teaching classical theory several times previously (here, here, and here – and spoken a bit here and here), this post is devoted to thinking about teaching theory differently. Moving forward, if you will. I offer five steps to begin to reconstruct a course on theory.

Step 1: What are your goals?

I think that people think hard about their syllabi. I have no doubts about that. But, how do we unlearn what our professional training has done to us? It isn’t really easy. Pick a top-10 sociology program, and you’ll find syllabi that reflect the 2 to 3 most vested-professors’ arbitrary (though seriously thought out) choices in readings and vision of theory. Generally speaking, they converge in some ways. Many, if not most, teach theory by presenting theorists they think are essential to being a sociologist. Bourdieu, Foucault, Marx, Durkheim, etc. From there, they engineer “theory.” Students generally learn little except that there were some big heavyweights, most of which (or usually all of which) are dead. Of course, in a “contemporary” theory, some “contemporary” theorists had the pleasure of dying more recently, and thus their writing is more approachable, while others died nearly two centuries ago and are impenetrable from the perspective of a 20-year old that struggles to read more than 240 characters (which is a problem in itself).

More recently, students may learn some heavyweights were predictably marginalized and should be considered more closely than the old heavyweights. Fair. Some may even learn that the discipline itself is a colonial project of imperalism and should be completely remade from the bottom up. Sure, I suppose this is du jour and somewhat cathartic.

While these choices have some rationale, when we step back and examine our goals, like what we really hope to impart, one usually hears buzzy terms like “critical thinking” and “sociological imagination.” All of these are fine goals, and I have no critique of those choosing to stick with this style, but what if we wanted students to learn theory and not theorists? What if critical thinking was only one small component of a goal to present a more coherent view of the social world? Not necessarily a mechanistic view, but one that actually showed the links between theoretical traditions and their explanation of things around us? Courses in social interaction do this all the time, tying units on meaning, emotion, language, self, identity, role, status, and interaction together. In other words, what if theory wasn’t painted as an inchoate body of ideas that represented imaginary camps of ideologically driven social scientists? Instead, what if we noted that there are core concepts that possess a significant amount of agreement in time and space and which underscore the sociological project. Theory is not a hammer, but instead a cumulative body of explanations being tested. (I realized, as an aside, some will say this is false, impossible, or secretly ideological. There is no amount of facts or evidence that will convince this group. The logic of praxis demands only some people have true consciousness, while their opponents – which far outnumber them – either need their false consciousness raised or are shills for the system. I’ve got news for them: sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.). I’m confident we can do this with the discipline or broad swaths of it more generally.

One might protest here and argue the primary function of the sociological imagination is in providing a lens to help students become good humans and citizens. A worthy goal, no doubt. But, teaching theory with little ideological, humanistic, or critical inflection can achieve this as well, if not better. The reality is the modal sociology student is already oriented towards justice, humanism, critical reflection. This is unfortunate, because we’ve become another echo chamber that rivals the one’s we rail against. We all “know” the world is a terrible place. That any progress made in the last 200 or so years is not enough, and that it won’t be enough until some imagined utopian ideal is built up. We know every person’s intentions are malicious, but not because they have agency, but because some sort of systemic pressure is their puppeteer. At least, that is, everyone but me and my closest friends. This is perhaps why the small, but exciting literature on joy is soooo radical! And, so necessary to combat a joyless sociological project driven purely by animus towards anything we deem an enemy, as opposed to balancing this by celebrating groups, solidarity, and effervescent interaction (whoa! Don’t be conservative Seth!).

Thus, at some point, you have to decide what we are doing. If we are busy teaching methods and stats, we should be using theory courses to teach students to use theory to motivate and make sense of their research. Empirical research is the weapon we use to critique the social world because it is rooted in the facts that provide ammo. Plenty of departments on campus and classes to boot are designed to inform students of the injustices of the world and the unfairnesses inherent in modernity, neoliberalism, capitalism, and other isms. Unfortunately, these “theories” are impossible to verify and, worse, impossible to falsify. Though some use them sophisticatedly as theoretical concepts, usually they are convenient philosophical positions about why things are bad and why one’s own vision of the world is morally better and one’s tribe is superior. John Levi Martin referred to this as sociological imperialism that lends a state-backed hubris to the Marxian notion that we somehow know better and are part of the vanguard party that will somehow shepherd our students to the promised land. To be sure, this is not a call for positivism or objectivism or other strawmen – if being proscience is positivist, then I guess that is a fair perjorative. Rather, it’s a simple point: we are in the business of describing, explaining, and, when possible, predicting social phenomena. The gold standard to work to is an explanation and subsequent testing of said explanation. When possible, policy-oriented sociologists may try to “control” or alter the environment, though that conversation is best left for another blog post, for another day.

Personally, in my experience, I find students get fired up when they are learning THEORY in the scientific sense. They are surprised we have theories, and that there are people empirically testing them, and that they can actually explain people, actions, situations, organizations, and so forth. The sheer diversity of theory boggles their mind. They are excited to learn we aren’t just going to talk about how capitalism is destroying the universe, but rather the social world has certain properties, even if the details vary. Communities, organizations, small groups, encounters, the self have generic components that make comparison possible and exciting, and which lend a sort of coherence to the rather chaotic world the discipline paints from one course to the next. All too often, theory is hermetically sealed off from most other courses, despite its required status in nearly all departments. This sort of obfuscation rooted in some sort of mystical, esoteric, pedantry hurts the subfield of theory and those who are trying to resurrect the idea of a theory specialist. That is why my students are pumped that what they heard theory was from friends – a dull class focused on large, dusty tomes that might as well have been written in Sanskrit – is not the course they are being exposed to. The class is not oriented towards trying to give up their inclinations towards justice or their activist aspirations if they have cultivated them already. Instead, they will have analytic tools to match these instincts and, perhaps, a sense of what they might do research-wise in a sociology dept.

Step 2: Figuring out what Level of Analysis Makes Sense

Now that you’ve clarified your goals, the harder work is ahead. This may not be a popular opinion, or even one that is even salient post-1990, but an effective theory course depends on figuring out the level of analysis you plan on working at. A slight digression to illustrate my argument. Durkheim’s classic text Suicide is famous for committing a major epistemic mistake: presuming that macro-level forces or phenomena (integration) can explain micro-level behavior (suicidality). The issue isn’t that integration has no relationship to suicidality, but that its causal relationship is dubious and nearly impossible to prove (or falsify). No need for hand-wringing on this gaping chasm in levels of social analysis. Macro and micro sociologies are just radically distinct in their logics; especially when working from the former “down” towards the latter. The issue is that sociologists have largely imagined these differences away. In part, that’s because our favorite theorists tend to work at the societal level, positing either grand, sweeping models or critical, philosophic treatises (e.g., Marx). We cannot really explain action at this level. It is for these same reasons Goffman is incompatible with macro-level theories, and suffers from the usual criticisms of not accounting enough for power, inequality, etc. And, when we see efforts to bridge or erase the yawning gap, it leads to conceptual gobbledegook and magical incantations like structuring structures and structured structures.

I don’t think there is a right choice here. I just think a theory course demands we come to terms with this problem and teach what we think is best for whatever reasons we can ascertain. Personally, I start at the very micro, thinking through the dynamics students can see – emotions, meaning, identities, status characteristics – and slowly move up to relationships, interactions/encounters, small groups, organizations, and communities. These “smaller” social units are ontologically real and are easier to touch and feel. Their impact on our self is also discernible. We can then talk about the structures and cultures that are invisible and distant from the everyday reality we experience. Think about how statistics and demography reveal patterns, and then ask the question about how these patterns and our biography intersect without presuming the former causes the latter; because the former doesn’t. To return to the Durkheim example: it is one thing to know that Protestants or unmarried men are at a higher risk of suicide than their counterparts, while it is an entirely different thing to ask why a given Protestant or unmarried man might be at risk of suicide. These questions demand local or more grounded contextual clues, as well as consideration of biological and psychological factors.

Of course, it is entirely legitimate to start at the macro. Sociology began as a comparative historical endeavor to understand how Europe became what it was. But, the properties and theoretical ideas from this large of a standpoint – both in terms of temporal and geospatial realities – is incommensurate with thinking about and talking about individual-level behavior. At least, that is my opinion.

In the end, you must stake out a position as these issues are bundled up with so many other issues related to global v. local, generic v. particular, diffuse v. specific processes. All of these binaries capture different elements of structure and culture and the challenges one faces when ignoring levels of analysis. Most of our social life, or what we even know is our social life and, therefore, the things that are causal, surround our everyday existence. Our family, friends, workplace, and so forth. The “global” leaks into our bubble through the internet and television, more than ever before. But, the idea that distal invisible forces are causing our behavior is a fundamental error in theorizing. Intellectuals think in universals more than the average person; they tend to cultivate wider networks covering greater geographic distances; and, like all people, they tend to impose their experiences on others. The local is where most of our life unfolds, relatively autonomously from the political and economic forces, sociologists imagine as puppet masters. That is not to say they have zero impact because surely they do. But, at the micro-level they are background. The theories that are useful for explaining these things, consequently, reflect this and, I think, are unfairly and prematurely maligned by a segment of the discipline for crimes they have not committed.

Conversely, if we are interested in describing and explaining a society in a particular time or over time, or comparing societies in one time or over time, then we need different tools. Cognitive and affective intra-personal motors are insignificant to the unit of analysis. Situations become too ephemeral and contained in time and space to have real impact. Instead, we are talking about massive aggregated changes that have little to do with why or how people do the things they do, but everything to do with describing and explaining society or, at the lowest macro-levels, organizations and communities (which are really meso, I think, but beyond the purpose of this post). Consequently, macro-level processes and forces, or theories, are more abstract, general, and challenging for students to fully wrap their heads around. They also demand a greater historical conscience that most students (and, unfortunately, many professors) possess, which makes pairing lively examples with dense theories difficult, though not impossible.

Again, no judgment here. I am relatively agnostic, and have theorized at just about every level. It took nearly two decades for me to come to terms with the incommensurability of macro and micro sociologies. For a long time, I figured I could paper over them, but as I stepped further outside of the conventional approaches to teaching theory, I recognized the two just were different – neither better than other, just different. In Step 4, I do offer a solution to avoiding choosing, but this solution is not necessarily the best choice. For now, the reader needs to think about what “sociology” means to them and what sociological theory is most useful for students. And, then, come to grips with the possible and impossible and accept the limits as ok.

Step 3: Read, Read, Read

I recognize the time crunches we all face. But, if one really wants to refashion and refresh their theory course, and transform it into something more than just the usual, then they have to read, read, read. Who has the time?!?! Make the time. The irony, I suppose, is we are all taught to read, read, read and subsequently keep up with our substantive area, but theory, well our backward necrophilic orientation makes it seem like these facts are facts: (1) knowing the dead people, and particularly those your advisor, colleagues, and favorite scholars worship, is enough to be a theorist or teach theory; (2) theory is not a subfield in the same sense as, say, race or immigration, and thus has no body of cumulative work; and (3) no one needs to read a lot of theory to know theory. None of this is true. A theorist or a theory professor needs to read widely, and should try to learn at least 7 to 10 of the major theoretical traditions (I’ll return to this in a second). As an experiment, I ask the reader to reflect on their own base of theory knowledge, and ask yourself if you’ve read and know all of these well enough to write a lecture on:

- Expectations States/Characteristics/Beliefs Theories

- Ecological Theories, both population level (Amos Hawley) and organizational (Hannan/Freeman)

- Affect Theory of Social Exchange

- Risk Theory (Ulrich/Luhmann)

I’ll leave it at those four, though I could add so many more examples. There is no reason to constantly dig up older deader dudes or dudettes when we have a lot of rich, empirically tested traditions! It is mindboggling that so many want to get into Hegel and Kant when Hawley’s (1986) theoretics and empirics are more refined and impressive than most classical sociologists (and many contemporary sociologists). I suspect some avoid or ignore him because he sometimes writes formally, throwing propositions into his work. Likewise, the microsociological status theories are so important, not least of which because they’ve developed a research program that has been testing Weberian-esque predictions for half a century. They have the receipts.

More broadly, our allergy to treating theory as a serious subfield stems from two obstacles; one that is likely not going to change and the other I think is changeable. The former is the stubborn inability to define theory in a consistent, coherent way such that most syllabi operate on a relatively shared vision of reality. I recognize that our inclinations as a field are to keep adding and including and expanding the base of both who is deemed a sociologist (I see you Marx) and what is deemed theory, but it has become untenable. There simply are too many people and epistemic systems that count as sociological. Some of these things rest on political movements du jour, some rest on the need to appear original or fresh, and some on the massive unknowable body of “theory” that ends up leading to so many blind spots in a given student’s sociology background that they invent new concepts when there are well-developed (but now forgotten) conceptual tools already existent. I also realize that I am swimming upstream when I argue that theory and politics are not aligned, at all. If one designs a course as a political statement or adopts some sort of ideological selection mechanism, they aren’t teaching sociological theory. Social theory, maybe, but not sociological theory. Thus, they probably aren’t reading this or they already disagree.

The second obstacle is far more manageable. It involves reading, extensively. I would begin by organizing readings based on a set of long-standing traditions:

- Classical Theory (everyone should know the basics, and nothing more unless they want to specialize in (a) hermeneutics or (b) history of social thought)

- Evolutionary/Ecological Theorizing – not only are these still alive and well, but they’ve become far less reductive over the last 20 years and are sites of cutting-edge theorizing

- Exchange Theorizing

- Symbolic Interactionist Theorizing (and Pragmatism)

- Microsociological Theorizing (includes Dramaturgy/Phenomenology/Ethnomethodology)

- Conflict Theorizing

- Structural Theorizing

- Culture-Cognitive Theorizing

This is a baseline and reflects the most common perspectives of theorizing since the classical era. It represents a cumulative body of traditions, all of which adopt scientific methods of varying kinds to examine and test their theories. In theory, one could design a course based on this list and whatever other bodies of theorizing I have unintentionally or intentionally omitted. But, once one has read enough in these areas, designing a course that is grounded in the depth and breadth of the discipline is far more likely than not. And, it will encourage fewer “names” and a more coherent tracing of concepts and ideas.

Consider, again, status characteristics theory (and its descendant, status beliefs). For nearly 50 years, this research program has been testing the theory in the literal sense of Kuhn’s “normal” science, slowly identifying the constraints and limitations of the predictive and explanatory model. A theory with 50 years of empirical evidence is a really mature theory, but two things block its path to greater notoriety. One is the bizarre belief that sociology is in the business of finding patterns until a pattern is found and then formalized, and then humans are far too creative, rational, original, random to act predictably. The hard science approach to theorizing turns people off. Two, there are some real biases against experimental work in sociology that are non-sensical and, to be honest, boring. Like other well-worn tropes grad students learn from their advisors about this theory or that, these exercises in critique are boring and are not really useful to anything other than keeping sociology in some strange chaotic status quo.

I digress. What makes status theories so great, is they are direct descendants of Weber’s own thoughts on status. Instead of using historical cases, they translated the logic of the theory into a microsociology, chose small task groups as one setting to examine the phenomenon of status, and used experimental methods to sharpen their lens. Nothing about the theory, besides its strictest adherents, prevents the assumptions, principles, or predictions from being applied beyond these conditions. It is a theory. Additionally, it not only pulls Weberian sociology into a course without having to teach only Weber, it also has clear links to macro theories of stratification, inequality, movements, and so forth. Ridgeway’s piece in 1991 brilliantly makes this clear (and, can bring Blau’s (1977) incredibly useful macro theory of differentiation and inequality back into the center where it belongs). Finally, I would add that theory is an excellent way to think through stratification without making sociology the science of stratification. That is to say, much of sociology today tends to be a contest over which axes of inequality are the most oppressive, when we should be specifying the dynamics of stratification, inequality, and oppression generally and then testing them in cases. These axes can be used as specific examples for the theory, offer correctives, or simply be reserved for the substantive classes that students will take that are almost totally consumed by them. Instead, arm students with the knowledge of (a) how status characteristics lead to expectations about behavior, reward, and competence that (b) create self-fulfilling prophecies for most people; (c) how repeated interaction in the same task groups can mitigate the most diffuse characteristics such that more specific ones become more powerful explanations for power and prestige in micro orders like work groups; and, finally, (d) how local groups can have counterintuitive power and prestige orders that do not reflect the societal stratification system, which while not disproving the impact of the latter raises really important sociological questions about members of the former. A student entering into a career in human resources or any organizational setting will benefit from being attuned to how task groups reproduce stratification systems and how they generate new, sometimes surprising, ones. If one’s job is making co-workers’ and employees’ lives better, more equitable, and just, understanding status dynamics seems imperative, rather than using the blunt oversocialized (conceptual) hammer(s) that most courses posing as sociological theory offer.

Step 4: Conceptualizing the Social World

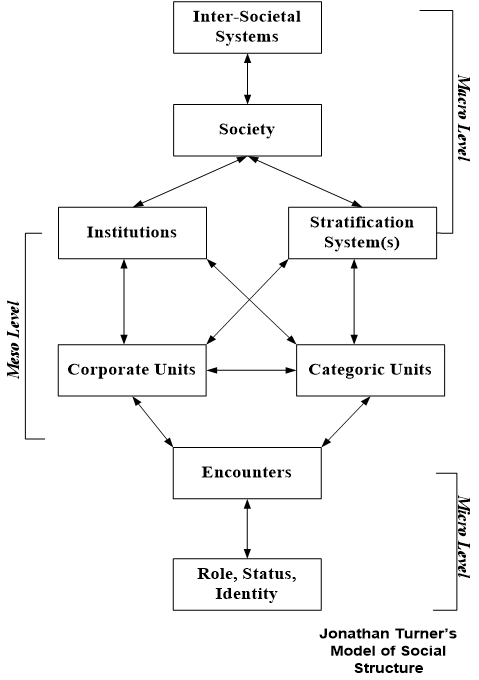

At this point, the strategy revolves around building coherence in your syllabus. This is the most theoretical task of the theorist. The teaching-by-theorist method or hybrids are not really intellectual labor, but rather the realization of dispositions long internalized in our sociological habitus. Deciding, as a scholar, what the social world looks like from your vantage point and then executing that vision through the careful curation of texts designed not to push a theorist or tradition, but to realize the vision is an art and science. Again, some of this will be constrained by the choices made in Step 2, and of course, Step 1. But, I think besides a few alternatives, I do not know of a better approach to connecting the readings to your own thinking to the discipline at large. Students will SEE this, and I will offer a money-back guarantee that they will respond to this (though, maybe not the first time you try this as there will be kinks you cannot predict just like any course development or revamp inevitably produce). I’ll give a short example of one strategy I’ve used in the past. The figure directly below this is borrowed from Jon Turner’s theory textbook. It is a simple heuristic device that visualizes the levels of analysis.

I begin every first class with this model, talking about all the different theoretical traditions and concepts that fit into these different boxes and levels of social reality. It is an anchor to which I come back frequently throughout the semester. I don’t buy it, wholesale, and I modify it as I see fit. But, it is a device that in its adoption implicitly and explicitly rejects the old way of teaching theory. It also suggests natural units or weeks of readings. One could design a course, for instance, on the bottom two boxes, their interaction, and the arrows from the two boxes directly above (corporate and categoric units). In a course like this, one might expose students to the various traditions listed above on interaction, pushing to ultimately show how exchange, dramaturgy, phenomenology, and other important microsociologists like interaction rituals or affect theory of social exchange contribute to understanding and studying the panoply of encounters we inhabit.

Alternatively, if macro sociology is one’s bag, one could think about those middle boxes and the boxes above them. A few weeks on social movements, for instance, start at the institutional and stratificational levels, noting how systematic inequalities mixed with oppressive machinations can generate new corporate actors (social movement organizations), which work backward on the macro-level. This allows for a survey of political and economic sociological theories, movements theory, stratification and inequality, and so on. One need only note, whether taking the first or second approach, the limitations of their strategy. We cannot explain individual-level behavior based on the second approach or see the full force and dynamics of the micro with the first.

The advantage of this approach is the scientific underpinnings and the avoidance of an overly functionalist bias. Instead, the student is provided a vision of how the social world is embedded at various levels, and how even the most micro or macro focus requires some thought about the other. The coherence, whether analytic or something one takes as ontologically true, supplies a more powerful working model for those interested in actually doing research. The questions one asks about self or groups or organizations can be easily sealed by the hermetical forces of subfields. Theory is, in the ideal, the force pushing people out of those vacuums. Consequently, a scholar of small groups must at least account for the individual-level dynamics and the broader corporate (e.g., organizational) and categoric (e.g., demographic characteristics of the corporate units) levels. It is holistic and represents a severe departure from the usual patchwork of sociology that is justified by some allusion to a ‘big tent.’

Step 5: Use These Theories to Craft Practical Assignments

Now what? The structure and substance of the course are designed, the last part is to try and link the ideas to something more practical. This is tricky. Especially with macro-level sociological ideas because, well, observing “society,” “systems,” “stratification,” or other “big” phenomena is really impossible. These are abstract concepts employed to study things that are tough to study otherwise, and like Durkheim’s integration or regulation, invisible like gravity; even if, sometimes, we can observe the consequences.

Here are three examples that do not exhaust the options. First off, despite their protestations, I always put students in groups that endure the whole semester (this is optional, but for the third assignment necessary). In groups, they do several different assignments linked to several different units. The simplest is on, at least most explicitly, stratification, inequality, and value. The class is arbitrarily divided in half, Two identical assignments, distinguishable only by an A group who are tasked with thinking about men and a B group thinking about women (this categoric distinction can be easily modified to suit one’s purposes). Students are asked to imagine they are the mayor of a town and have $500,000 to divide among 10 occupations (if you give them too much money, it becomes much more complicated). The occupations I use are from a workbook I snagged this from, but can be changed. The money needs to be somewhat difficult to divide, otherwise hard choices and implicit biases cannot be triggered. The occupations: medical doctor, professor, kindergarten teacher, cop, farm worker, fast food manager, trash collector, EMT, athlete, and bus driver. After distributing the money, students are asked a series of questions culminating with a reflection question about how theory helps us understand their decisions and what this tells us about American (and now Canadian) society. As a group, they must work through a second worksheet, coming to a compromise about how to divvy up the money and answering similar questions. I have a decade’s worth of data from this, with a few interesting things I can show them after I walk them through the class averages, mode, median, and a few anonymized qualitative responses. (For instance, the gender differences in, say, medical doctors or professors are much less pronounced in Canada than in the States). It raises some really cool discussions about class, status, inequality, and so forth. (Especially when the inevitable 2-3 students divide the pot equally and are forced to defend the choice, which is a great moment in class conversations).

Second, after reading/discussing work on integration, interaction rituals, and so forth and then during the unit on encounters and local culture, students break into teams of two from their groups of four and find a fieldsite to sit and observe. A dry run is designed to practice doing field notes and observation, while a second run is meant to record data on what’s happening. The smaller groups each work independently, initially, and then debrief together about what they both saw, what unique things they caught, and what this says about the field site and about the researchers themselves. In some cases, I’ve modified this assignment to push one member of the two-person group to be a participant in the action while the second is just an observer; then, they flip these roles. They are even encouraged to breach if possible.

Finally, the third assignment is more meta and returns to status expectations theory. When the groups are assigned, I save 10 minutes of time on the first day of class for them to exchange phone numbers, create WhatsApp or text message groups, and chit-chat. They each have to fill out a worksheet asking them for their snap judgments about each group member and their likely contribution, etc. I do not tell them what this assignment is about and, because it occurs long before the status expectations lectures/readings, it is unlikely to be something explicitly on their mind. The goal is to think about how we evaluate others in our first impressions and what markers trigger our biases. Subsequently, each time they do a group assignment they fill out the same worksheet that also asks them to reflect on the previous worksheet and whether things have changed, stayed the same, surprised them, and so forth. The last worksheet comes after they’ve had the full status expectations lecture, and thus adds more theoretically-informed questions along with questions about what they’ve learned and whether they’ve carried these tools beyond the classroom. It is key to remind them in person and on the sheet that they are not to share this with anyone, that you will not share it with anyone, and that their grade is independent of the group’s “success.” Not all, but many “get” the assignment and write some really reflective, penetrating things.

Each of these assignments are designed, then, to get the students to observe their reality – not some “distal” reality, like the news or current events or whatever – through the tools being provided. That was, in effect, Garfinkel’s goal with the breaching experiments (which I also use, but perhaps felt that was too obvious to include here). The experiential piece pushes back on the “sociology is common sense” bit, as yes, many things are obvious to them, but reflecting on why and what it means is the step beyond the concrete to the abstract that is necessary to moving towards theorizing.